One More Time on the Economy

Three different arguments happening simultaneously is leading to a conceptual mess.

Ihave been closely monitoring the recent discourse on the goodness of the economy (I, II) and I think I’ve fully mapped it out and understand why it keeps breaking down. What is being presented as an argument about one question is actually an argument about three different questions:

Is the economy good?

Did Joe Biden do a good job with the economy given political constraints?

Why do people say the economy is bad when asked by survey takers?

Each of these questions is interesting when analyzed separately. But when you mush them together without realizing you are doing that, you end up in a rhetorical quagmire that causes frustration and confusion.

My interest in the debate is mostly on question number one, i.e. whether the economy is good. When I was introduced to this discourse, this seemed to be what people were arguing about, with the consensus sentiment from liberal thought-leaders being that the economy is not only good, but is extremely good, and that any viewpoint to the contrary is bad faith, borderline insane, or factually bankrupt.

I found this peculiar because whether the economy is good or bad is, at minimum, a highly contestable question that turns as much on your ideological views about what makes an economy good as it does on various factual indicators.

If we take a snapshot of the current economy and ask whether it is good or bad, certainly anyone with conventional leftist views on economics would say that it is bad. The welfare state is bad. Unionization is low. Public ownership is low. Inequality is high.

This negative assessment is not based on some pie-in-the-sky baseline for a good economy either: we hugely trail many of our developed-nation peers on those metrics. Nor is this baseline being opportunistically selected: the left spent five years lining up behind a Bernie Sanders campaign that had as its core premise that an economy that looks like what we have right now is really awful.

If we look only at recent changes in the economy, what we see is a very mixed bag. On the one hand, the recovery from the COVID recession has increased employment and compressed the wage schedule, both good things. On the other hand, the rollback of the COVID welfare state has seen free school meals eliminated, cash benefits for the poorest kids eliminated, 10 million people kicked off Medicaid, and the return of our completely dysfunctional unemployment benefit system, all bad things.

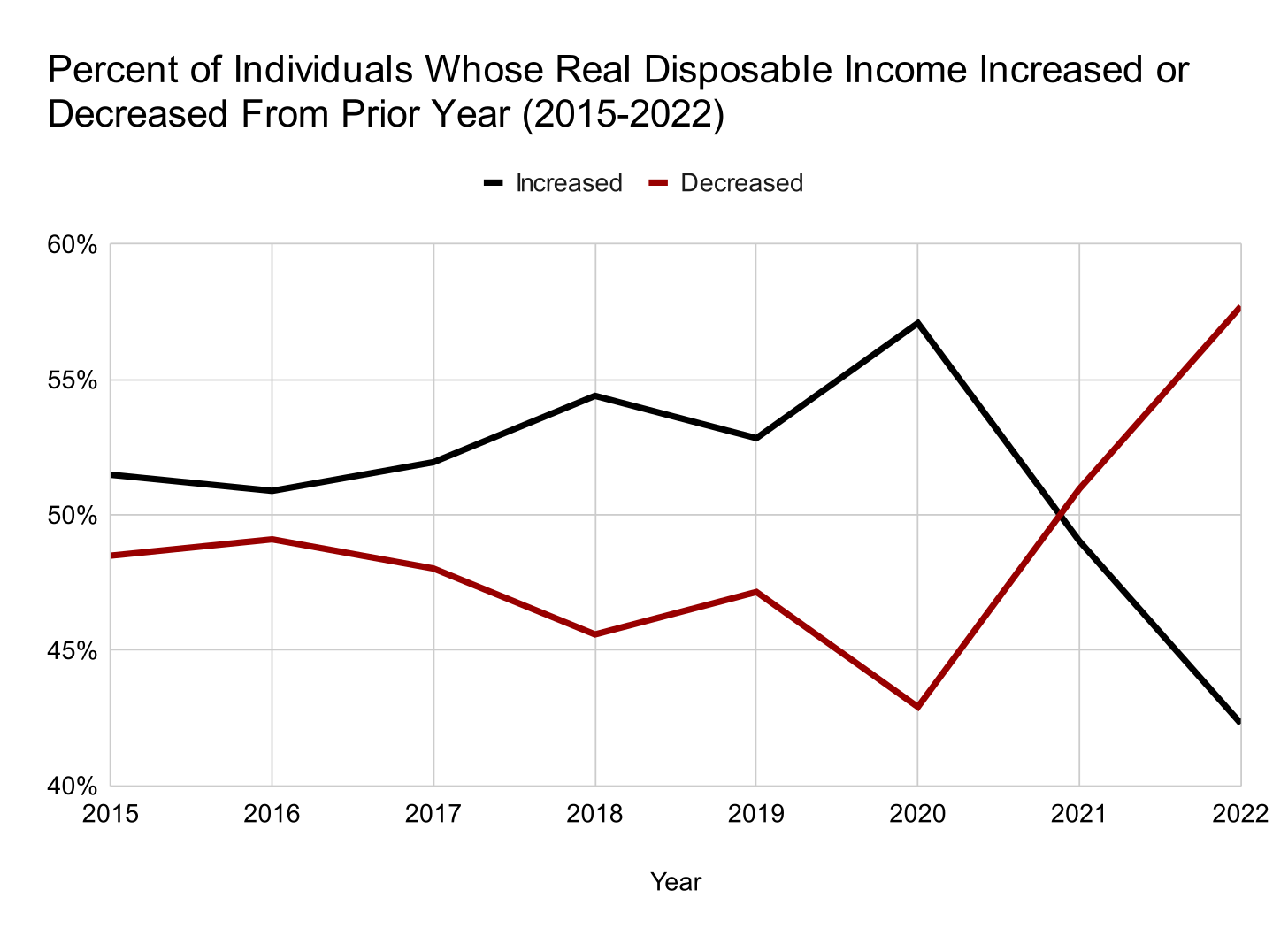

The question of how exactly to combine these conflicting developments to generate a net assessment of recent changes presents the usual incommensurability problems and therefore heated debate. My simple attempt to net this all out by looking at recent developments in disposable income is presented in the graph below. This disposable income concept includes labor market and welfare state developments in it, but it does not fully settle the debate either.

As I have proliferated this argument over the past few weeks, what I have found is that people respond by changing the subject to questions (2) and (3). So they acknowledge that obviously social democrats must think the current economy is bad and must think that these recent welfare cuts were bad, but then say either that these things are not Biden’s fault or that survey respondents who say the economy is bad are doing so for other reasons.

These latter two questions are of much less interest to me, in large part because there is no real good way to argue about them.

The genius of a government with so many veto points is that it’s impossible to assign blame or credit to anyone for almost anything because no single person or government body is a necessary and sufficient cause of most government actions. In practice what this means is that partisans credit the president for everything that passes even though he cannot unilaterally pass anything, but do not blame him for anything that fails to pass because, after all, he cannot unilaterally pass anything.

As to what motivates survey respondents, it’s clear enough that a lot of survey responding is “expressive” in the sense that people don’t attempt to answer the question that is presented to them but instead, consciously or subconsciously, use the question as a proxy for things like “do you like the president” or “how do you feel about the state of the country” or similar. The funniest example of this I have seen is that, shortly after Biden was elected, the percent of Democratic survey respondents who said they felt financially comfortable buying a new refrigerator massively shot up.

A couple of years ago, it became popular to dismiss polling that showed people liked progressive ideas by saying it was unreliable. But weirdly those taking that position presented as their alternative other polling that worded questions about these ideas differently in order to generate more negative responses. Now it seems maybe they are finally coming around to the more natural conclusion that topical polling is itself meaningless, not just when it shows support for public health insurance.

In any case, as interesting as questions about Biden’s culpability and survey behavior is, it is important not to conceptually muddle them with the question of whether the economy is good. Proving that Biden did the best he can and that survey respondents are stupid or expressive does not actually prove that the economy is good. By conventional social democratic measures, the economy is bad and recent trends in the economy have been mixed at best. Any conclusion to the contrary is therefore based on ideological, not factual, disagreement.